Bitch Formalism

Bitch Formalism is an attempt to use form to question the relevance of gender in art. It is playing with “feminine forms” in a gendered context to ask the viewer to question assumptions. The term “Bitch Formalism” was coined by artist Dana DeGiulio, when she encountered my piece Hand Catching Cupcake — a piece that plays with ideas of gender in response to Richard Serra’s work Hand Catching Lead.

Bitch Formalism, A treatise by Dana DeGiulio, 2016

Bitch Formalism

Cuts the fat, all the way to the bone.

Laughs. Understands laughter as an hydraulic that relieves the organism of the responsibility of actual violence.

Is tactical, impatient, un-shy.

You see it all at once.

Requires you to take a side. There are only two, and one is against us, and they are equally correct for the risk of your decision.

Its bodies, having been humiliated, are without shame.

It holds the negative.

Rhetorical, cynical and without "ideas."

The arms aren't open. They're empty.

The edges stay hard.

Bitch Formalism could stand to hold you and in fact does but also defies, deflects, resists openly, awfully, cheerfully, any release but your laughter.

Heuristic. All the tension of a metronome.

Is located in history, and posits everything equal at the level of species and variant at any degree of acculturation. Except for potential and its silencing, about which it is aggrieved and cannot avenge and so in this way works for the past.

Anti-verbal, unless it is verbal, and even then.

Anticipates nothing of the intelligence of its interlocutor but knows

their scale.

Repeats itself.

Only asks.

Insists that nothing is exhausted but that everything is already over.

This makes us free.

Innocence is not a position.

Goes assforward into the future, anus-eyeball focused straight ahead, understanding that apprehension requires a fully occupied and open sensual apparatus, and alert to history, facing it.

Bitch Formalists are waiting without hope or fear, but never for you.[i]

So Bitch Formalism is a standing-away from the default: patriarchy. It attempts to capture and illuminate inherent conflicts of being — violent and playful; open but empty; humiliated and without shame — that exist for all, but specifically within the context of being a woman. To go “assforward into the future” is what it is to feel the world is backwards — made for someone who is the opposite of you. It is what is left, as the minority position, when there is the realization that there is a dominant position and it is not available to you due to circumstance. Bitch Formalism looks from a different angle — a backwards angle that has seen the other side and has rejected it and been rejected by it. It is a silly, serious, angry, laughing, forgiving, judgmental thought that holds a truth.

Bitch Formalism, although a new term, is not a new idea. Anyone using material to comment on gender is playing with these concepts — Louise Borgeois with her soft sculptures, Yayoi Kusama and her use of fabric and environment. And Queer Formalism is a similar call to look at art from a different perspective in the hopes of understanding something that does not fit neatly within existing social/cultural categories.

My Work with Bitch Formalism

In these pieces I examine gender in the context of some of the big names from the Abstract Expressionist period. Hand Catching Cupcake is a response to Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead from 1968.

Hand Catching Cupcake, three minute video, 2015

https://vimeo.com/186116750

In Hand Catching Cupcake, I draw attention to gender by using humor and play. Richard Serra’s Hand Catching Lead is a simple, three minute, black and white film of a man’s hand catching pieces of lead. The “default” assumption that I wanted to challenge in Hand Catching Cupcake is that the white male is a neutral representation for all humans, regardless of race or gender. Serra titled his piece Hand Catching Lead, assuming that the "hand" was somehow neutral. But the industrial setting, the rolled up sleeve of the work shirt, and the muscular white hand attempting to catch sharp pieces of heavy lead exude a decidedly masculine tone. My equal but opposite Hand Catching Cupcake — placed in a domestic setting, the feminine hand with wedding ring attempting to catch pink-frosted cupcakes — exudes a stereotypically feminine tone.

This work invites the viewer to examine the gender spectrum, to ask: if Hand Catching Lead is 100% masculine and Hand Catching Cupcake is 100% feminine, then where do I fit? Are these distinctions even real? I also wanted to question assumptions about what it means to be a man versus what it means to be a woman in our society. Culturally, men are expected to be solid and deal with edges, while women are expected to be soft and deal with home. But is this really true? What (or who) gets excluded when we view art through the narrow, entitled filter of the patriarchy, when the protagonist or artist is a straight, white male? How do we diminish, dismiss, or deny our own multi-dimensionality when we forget that we are all “equal at the level of species”?

Holding, or Bowl in the Shape of a Robert Motherwell painting, 2016

15” x 12” x 6” based on Elegy to the Spanish Republic

Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic paintings are about war and death. They are huge in size and are often likened to marching soldiers. Because of the feminine connotations of Motherwell’s name, I was curious to examine the shapes of his work within a “feminine form” — a bowl. I wanted to create an equal but opposite portrayal with what is often considered feminine or craft material: clay.

The piece is small and ceramic and therefore fragile. If we take these same black forms and make them into a handheld bowl, they no longer seem like marching soldiers but become something that holds emptiness. I wanted to look at holding, nurturing, “mothering” (considering Motherwell’s name), and his themes of death and war. What are our ideas about war and women? How do we experience the emptiness of war? What roles do holding and emptiness play with regard to gender? How do we experience the small, quiet, healing spaces versus the large, uncontained expanses of the battlefield? Doesn’t everyone have the capacity to be nurturing, quiet, small, and fragile while also dealing with death and war on some level?

[i] Dana DeGiulio, “Bitch Formalism.” Facebook post, February 22, 2016.

If Brice Marden Was Born a Woman

Brice Marden is an American artist born in 1938. He comes out of the Abstract Expressionist (AbEx) ideals but is often considered a minimalist. In the late 1960s Marden gained fame for painted monochromatic panels. In the 1980s Marden’s work changed to incorporate calligraphic lines created with long sticks from a distance. His work, like the Abstract Expressionists, is created intuitively (without a clear conceptual plan) as well as being a formal exploration of his experience of color, light, and architecture from his many travels to Greece and Asia.

Marden, Epitaph Painting 5 1997-2001 Oil on linen 108 1/2 x 104 inches

Brice Marden stick drawing

I was curious to look into Marden’s work because my work is often compared to his. We both explore color, transparency, and line, so I was interested to see how he works and where he comes from.

What I discovered is that he has a strong lineage connected to the AbEx movement and to the history of American art in general. Marden talks about being deeply affected by Rothko as well as Jasper Johns. He also worked as an assistant to Robert Raushenberg for 4 years towards the beginning of his career. So in essence he has a clear pedigreed within the American art we learn about in school.

It made me wonder how his career might have played out differently had he been born a woman. What are the specific opportunities that would or would not have been available to a talented female painter named ‘Bryce’ in the late 1960s?

“Bryce” Marden – A Chronology

Probably the easiest difference to see between a male Brice and a female Bryce, would be with regard to money. Brice Marden’s last painting sold for $10.9 million in 2013. The highest sale I can find for a woman artist was in 2011. Cady Noland sold a painting for $6.6 million – which “broke the record for the highest price ever paid at auction for a work by a living female artist.” The painting was expected to sell for around $2 million.[1] So it’s not a big leap to assume that Brice (the man) would earn quite a lot more than Bryce (our imaginary female equivalent). That is about average for what women earn compared to men in the US in general – about 77%.

The pay difference between men and women is easy to document but there are many more grey areas that affect work, life and success. For example if Brice has been born Bryce, would she have gone to Boston University in 1958? In the 1950s there were still a lot of universities that didn’t accept women. But let’s assume that yes, Bryce attended Boston University. BU was way ahead of other schools being the first university to open all divisions to female students at the early date of 1872.[2] But I don’t know that she would have gone to Yale for an MFA in the 1961 after just having a child in that same year (the year Brice Marden II was born).

As Eva Hesse wrote in her journal around the same time: “A woman is side-tracked by all her feminine roles from menstrual periods to cleaning house to remaining pretty and ‘young’ and having babies.”[3]

But for arguments sake, let’s say that Bryce chose not to have a child that particular year and instead got that MFA at Yale (who did accept women into the Fine Arts department since 1869 although not to all departments until 1969.)[4]

Big problems start to pop up in 1964 when Brice worked as a part-time museum guard at the Jewish Museum and spent a lot of time in the Jasper Johns’s retrospective – a time he attributes as an influence in his developing work. Women in the 1960s could still not get a credit card without a husband to co-sign for them or serve on a jury[5] and even though ideas were changing many fields were not open to women yet. I doubt the job of ‘museum guard’ was often if ever filled by a woman.

So the important Jasper Johns influence would be gone. Spending hours each day looking at Johns’ paintings would affect the work of Marden but not our imaginary Bryce. It’s impossible to know the effect of that time, but it does point to complex problem of opportunity. Through no malicious intent by anyone opportunities can be missed by women. Underlying ideas of what a woman can and can’t do affect not only what job she might be hired for but for what job she would even think to apply for.

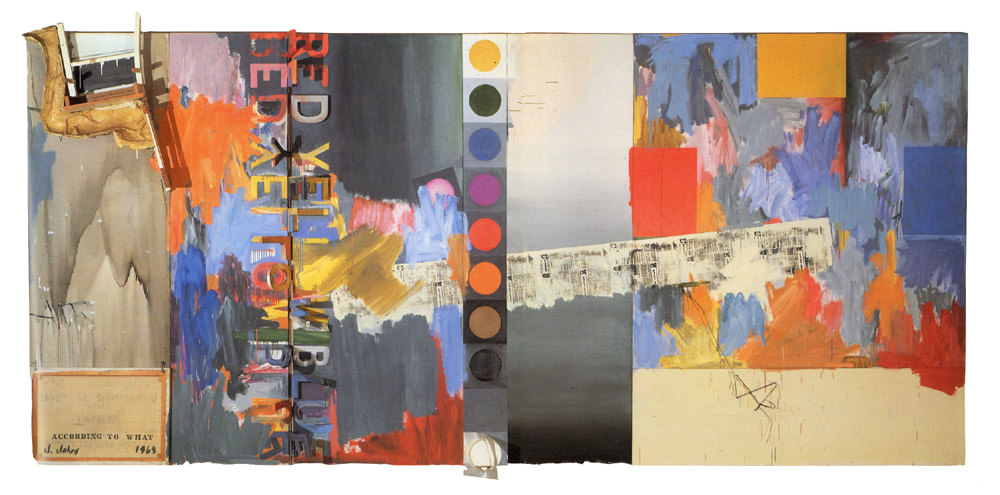

Jasper Johns, According to What, 1964

But even if Bryce was not a museum guard, she still could have traveled to Paris and created some of her first grid drawings in the late 1960s – an important precursor to later work. And there’s no reason the female Bryce wouldn’t have been employed at a silkscreen workshop where she became friends with Harvey Quaytman who suggested mixing beeswax and turpentine into paint – an important technique that was part of Marden’s work. Although in retrospect art historians would have wondered if Bryce and Harvey had had an affair of any kind since Quaytman was recently divorced. And if they hadn’t had an affair, then they would have wondered if either Bryce was a lesbian at the time or if Harvey Quaytman was secretly gay.

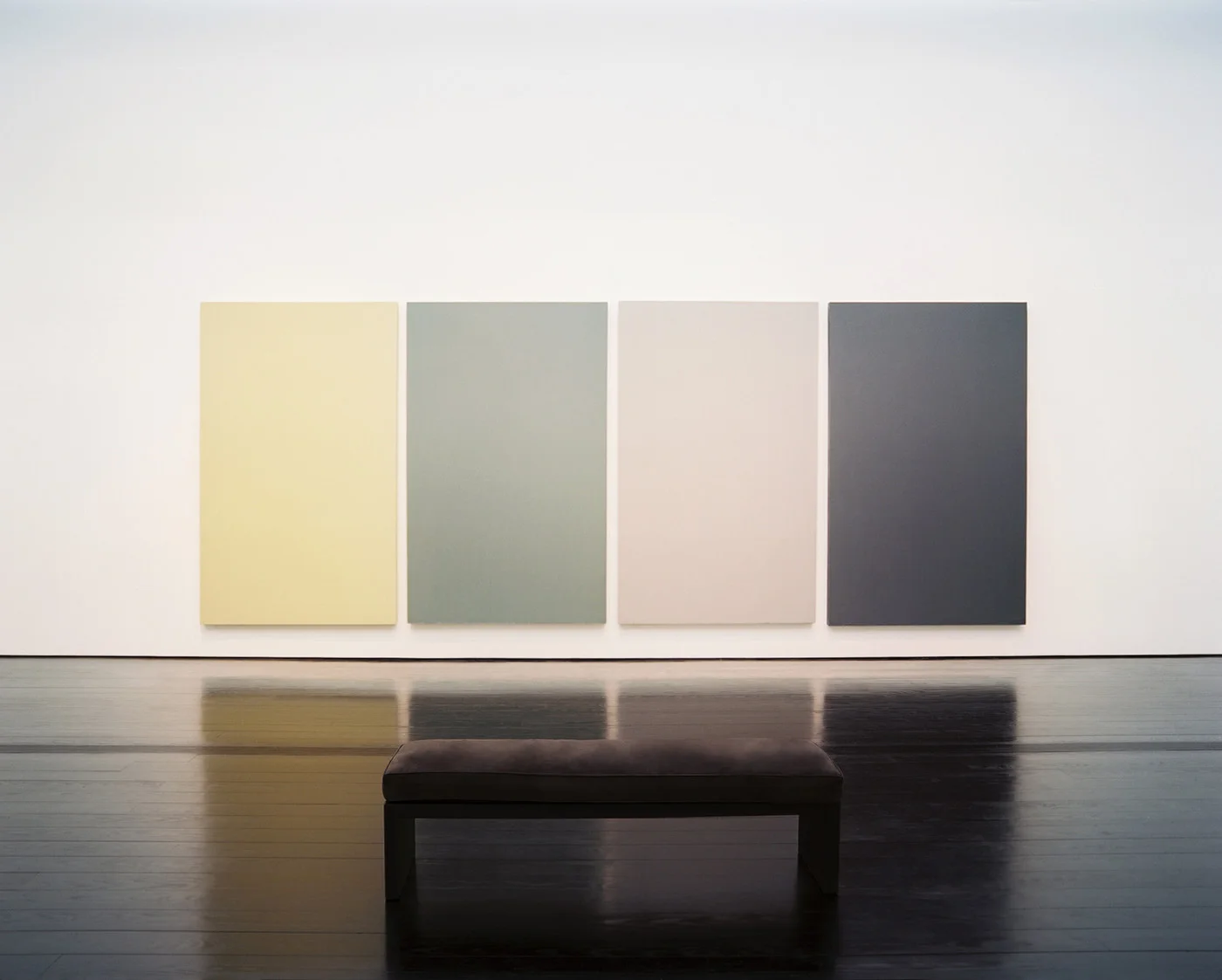

Untitled - Brice Marden

The biggest question in the history of Brice Marden’s life would be if Bryce, the woman, would have ever been hired as Robert Rauschenberg’s assistant. This was at a pivotal time in Marden’s career and would have introduced him to many key players in the art world. Marden describes the time with Rauschenberg; “Technically you’re his assistant, but also you’re being paid to sit around and drink with him… [Rauschenberg] was very lonely then, and sort of shaky.”[6] This is what some consider Rauschebberg’s “dude period” – drinking and traveling, wearing a porcupine-quill jacket and long hair.[7] Rauschenberg, who we now know was gay, did have close women friends – he was very close with Susan Weil, an American student he met in Paris and followed her to Black Mountain College.[8] So it’s possible he would have hired a female assistant but I can’t find any record of him ever having a female assistant. I can find a number of male assistants – the most famous of course being Brice Marden. So I doubt that the role of assistant would have been filled by a woman – even if her main duties were just sitting around talking.

So if our female Bryce was never Rauschenberg’s assistant that would have veered her way off of the male Brice’s course. That first year as Rauscheberg’s assistant was also Brice Marden’s first solo show. We can’t attribute that to the connections he was making by working for Rauschenberg but it seems likely that it would have helped. More people in the right places would have been in place to see what Marden was doing so the people and places he would have had access to would have changed the game.

I also wonder at the reception of Bryce’s work in the 1960s and '70s without those connections. Many of Marden’s first works were single colored canvases. Could a woman have gotten any attention in the late 1960s with these grey color field paintings? Helen Frankenthauler was working at that time but her work was much more vibrant and colorful. She was also 10 years older than Marden and more established possibly due to the fact that she was born with money and involved with a number of important male figures in the art world – Clement Greenburg, Robert Motherwell. Bryce, coming from a more modest background would have possibly had a harder time gaining attention as a woman with such subtle work. That initial spark that starts an artist’s career might have been harder to find for Bryce than it was for Brice.

Brice Marden, The Seasons, 1974 - 75

AbEx

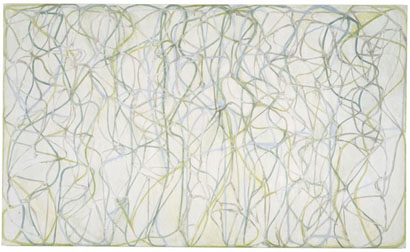

Amy Sillman – a female painter (born in 1955) that is often connected to AbEx – had an interesting take on the gender complexity of AbEx:

“How is it that, despite the complexity of AbEx, its reputation has boiled down to the worst kind of gender essentialism? Its detractors would have it that the whole kit and caboodle is nothing but bad politics steel-welded around a chassis of machismo – that the paint stroke, the very use of the arm, is equivalent to a phallic spurt, to Pollock whipping out his dick and pissing in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace. (This sexualized reading is itself, of course , a reversal of Clement Greenberg’s earlier – but no less testosterone-driven – notion of AbEx as a pure and transcendent optical experience.) Meanwhile, AbEx’s legacy presents us with a tangle of still more gender clichés, a strange terrain inhabited by fake-dude-women like Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell, wielding their paint sticks with cowboys; and Pollock and de Kooning operating as phallic she-males, working from their innermost intuitive feelings, a 'feminization' that introduces another twist in this essential logic.”[9]

Amy Sillman, Untitled, 2012, oil on canvas, 51 × 49 inches.

Surprisingly, Marden responded to this article in an interview he did for a magazine. The interview was conducted by his daughter, Mirabelle Marden, an artist and curator.

BRICE: I came out of the abstract expressionists. That was who I was looking at when I was a student and that is what seemed to be the important thing. And I was involved with a lot of this catharsis and—

MIRABELLE: Anti-establishment.

BRICE: Yeah. But then I read Amy Sillman, who complains about this whole macho aspect of abstract expressionism. I was totally shocked when I read it all.

MIRABELLE: How could you be shocked by that?

BRICE: I thought, "Oh my God. She's absolutely right." I should have been asking Ruth Kligman [painter and muse/lover to Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning] important questions. She was involved with all these guys, and she was no dumbbell. The point is you're involved with ideas. And arguments arise.

MIRABELLE: How can you not be involved with your ideas? What's the point otherwise?

BRICE: That's true. Or else it's just product. And product is something that's made to make money.[10]

When Mirabelle asks “How could you be shocked by that?” I think we see a glimpse into the experience of being a white male. To be excluded makes you aware and Brice was not excluded – so how could he have noticed the machismo of AbEx? He was too busy being part of the idea to notice who was being left out.

Which brings me to this part of Amy Sillman’s quote: “Clement Greenberg’s earlier – but no less testosterone-driven – notion of AbEx as a pure and transcendent optical experience.” If Brice Marden had been born a woman she may not have even been that interested in AbEx. The movement tended to exclude women and the women that were involved – Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell – had to develop either a form of aggression or move out of the country to find their own way. Maybe Bryce wouldn’t have been that aggressive – Brice certainly seems like a laid back kind of guy - and would have not felt herself represented in the AbEx movement. Maybe she would have been more attracted to the Agnes Martin minimalism route.

Woman's Work

I think whether man or woman, Brice Marden was compelled to create and would have done so. I think the main difference between the life of Brice and Bryce would have been the amount of support that would have lead to success in the art world - not only opportunities to show work but also opportunities interact with other artists and grow as an artist. Even though many of the art schools at the time had a high percentage of women students, the number of women showing in galleries and museums was very small. There are no doubt myriad reasons for this, but one of the main outcomes, it seems to me, is a lack of structures and lineages that women could follow either then or now within the art world.

In an essay on the problems of installing feminist work, Helen Molesworth writes about Dana Scultz’s work and her quick rise to prominence:

“Although the body is a perennial feminist subject, Schutz, for the most part, was not discussed in terms of a tradition of feminist work; rather her newness and youth were offered as the primary filters through which to approach her paintings. Part of her meteoric rise, therefore, was tied to the way her work appeared unconnected to artistic precedents. This amnesia, although prevalent in the current market-driven art world in general, is largely not the case with young male artists, who are quickly legitimized into comfortably entrenched art-historical narratives, given fathers by their critics. This makes sense given that the average museum’s presentation of its permanent collection is an offering of pluralist harmony (one good picture after another) intermittently punctured by Oedipally inflected narratives of influence, in which sons either make an homage to their fathers (Richard Serra to Jackson Pollock), kill their fathers (Frank Stella to Pollock), or pointedly ignore their fathers (Luc Tuymans to Pollock).

“Genealogies for art made by women aren’t so clear, largely because they are structured by a shadowy absence.”[11]

I would venture to say that this shadowy absence also works in reverse for female artists while developing their work. Who are our art-historical mothers? And how are we to find them if they are so rarely shown in galleries and museums? As a woman you are expected to be influenced by male art-historical figures. But how often are men expected to be influenced by women art-historical figures? And if they are, do they ever mention it? I have never read of a male artist being deeply influence by Georgia O’Keefe or Mary Cassatt. So Bryce, a female artist working in the 1960s, would have been left with far fewer historical figures to look to who were female.

Which brings me to the idea that if Brice were a woman all of her work would be seen through the lens of femaleness. That even if the work were identical – which due to the changes in circumstance (i.e. not working for Rauschenburg or spending time with Johns paints) it would probably not be – the criticism around the work would change considerably. As Molesworth says above, “the body is a perennial feminist subject” and as such when a painting is done by a woman, the artist’s body is seen within it. And yes, many women artists are commenting on the cultural experience of having their identity wrapped up in being objectified as a body in a male dominated culture. But even abstract artists are told that their work is about bodies if they are women. And I would venture to say that Bryce’s work would be thought of as very bodily – with curved lines and abstract dancing muses. And specifically she would be seen as identifying with the muses as opposed to Brice Marden who would be seen as thinking about what Muses are and what they mean.

Brice Marden The Muses, 1991-96; Oil on Linen

It seems that throughout art history a woman paints a representation of her body, whereas a man paints beauty which is represented by a woman’s body. Even when men paint or sculpt a male body it is often seen as an object of desire to the artist not as a representation of exploring his own body. Women are seen as sensual creatures, men as thinking creatures. I would venture to guess that the entire concept is false. Men and women both have bodies. When Amy Sillman paints is she painting from her bodily experience more than Brice Marden? They are both engaged in an intuitive dance – following thoughts and impulses to create work. The entire idea feels culturally placed on top of the work, reinforcing a subtle sexism where Amy Sillman is seen as less intellectual and more sensual and Brice Marden is seen as exploring ideas not sensual experiences.

Brice Marden, Orange Rocks, Red Ground (3), 2000-2002.

If Brice Marden were a woman her colors would be praised more often for their vitality and her lines would represent her sensual experience. Her subtle layers would represent the layers of being a woman – the erasing and rewriting of her personal history or of adapting her life around men and children. She would be a pioneer in feminist work because she continued to work when no one was paying any attention to her for 20-25 years.

My hope is that even if Brice had been born a woman her work would still have been found and celebrated – but that is the question… How many female artists have we lost along the way? And even as large institutions go back and rewrite history (in the good way) by placing female artists within the canon, how do we pay attention to women artists in a new way? As Helen Molesworth writes: “part of what I’m after, as a feminist, is the fundamental reorganization of the institutions that govern us, as well as those that we, in turn, govern.”[12] How do we, as a culture, change our thoughts, actions, and their meaning from the inside out?

___________________

[1] Rozalia Jovanovic, “Who Are the Top 10 Most Expensive Living Women Artists?” ArtNet. May 6, 2014. https://news.artnet.com/market/who-are-the-top-10-most-expensive-living-women-artists-12590.

[2] “Our Place In History.” Boston University Admissions. http://www.bu.edu/admissions/about-bu/history.

[3] Lucy R. Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York: New York University Press, 1976), 205.

[4] “Landmarks in Yale’s History – 1969.” http://www2.yale.edu/timeline/1969/index.html.

[5] McLaughlin, Katie. “5 Things Women Couldn’t Do in the 1960s.” CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2014/08/07/living/sixties-women-5-things.

[6] Richardson, John. Sacred Monsters, Sacred Masters. New York: Random House, 2001, 305

[7] Richardson, John. Sacred Monsters, Sacred Masters. New York: Random House, 2001, 305

[8] “Robert Rauschenberg: American Collagist, Painter, and Graphic Artist.” The Art Story. http://www.theartstory.org/artist-rauschenberg-robert.htm.

[9] Amy Sillman, “AbEx and Disco Balls: In Defense of Abstract Expressionism II.” ArtForum (Summer 2011), 321. Accessed December 5, 2015. http://www.amysillman.com/uploads_amy/pdfs/abex.pdf.

[10] Mirabella Marden, “Brice Marden.” Interview Magazine, January 5, 2015. http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/brice-marden/#page3.

[11] Helen Molesworth, “How to Install Art as a Feminist.” In Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art, edited by Cornelia H. Butler and Alexandra Schwartz (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 504.

[12] Molesworth, 499.

Additional References

Costello, Eileen. Brice Marden. New York: Phaidon Press, 2013.

Garrels, Gary. Plane Image: A Brice Marden Retrospective. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2006.

Kertess, Klaus. Brice Marden: Paintings and Drawings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992.

Molesworth, Helen, ed. Amy Sillman: One Lump or Two. Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2013.

Petrovich, Dushko and Roger White, eds. Draw It with Your Eyes Closed: The Art of the Art Assignment. New York: Paper Monument, 2012.

Purvis, Cynthia, ed. Brice Marden: Boston. Boston: Museum of Fine Art, 1991.